I once worked with an organization that was genuinely trying to improve how it delivered strategy. There was no belief that it had “figured out” transformation governance. In fact, the opposite was true. The leadership team recognized growing complexity, delivery strain, and inconsistent outcomes, and responded the only way many large organizations do — by adding structure.

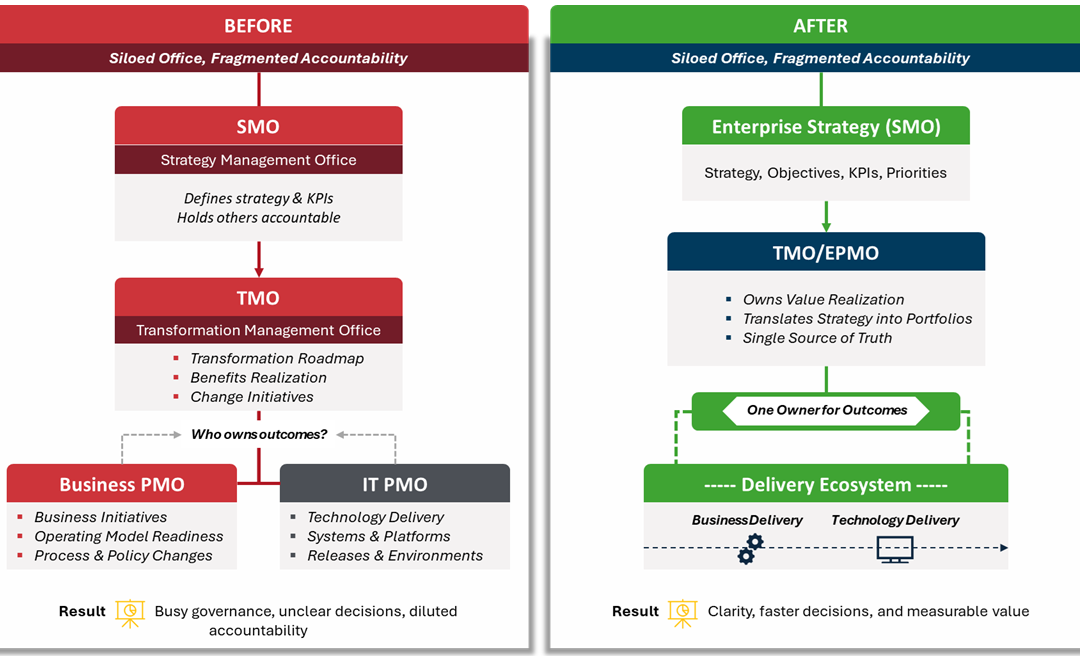

Over time, a Business PMO, an IT PMO, and a Transformation Management Office (TMO) were established. Each served a clear purpose at the time. As strategic ambitions grew, a Strategy Management Office (SMO) was later introduced to strengthen strategic direction, performance tracking, and enterprise-level accountability.

Individually, each office made sense. Collectively, they were expected to form a logical flow from strategy to execution. The problems only emerged once they had to operate together.

As execution progressed, tensions surfaced. The SMO questioned delivery progress based on strategic KPIs. The TMO, accountable for delivery, often faced constraints beyond its direct control, particularly where initiatives spanned business and technology. Conversations gradually shifted away from how to unblock delivery and toward who ultimately owned the outcome.

The SMO was responsible for defining strategy, setting objectives, and tracking performance at the enterprise level. The TMO was accountable for delivery — coordinating the transformation roadmap and ensuring initiatives progressed in line with strategic intent. In theory, this separation should have created focus and clarity. In practice, the boundaries between strategy oversight and delivery accountability were never explicitly designed.

At the delivery layer, the Business PMO and IT PMO operated largely in parallel. Many initiatives were business-led but technology-enabled, yet governance treated them as two separate streams. The Business PMO tracked operating model readiness, policy changes, and stakeholder alignment. The IT PMO tracked system delivery, releases, and technical dependencies.

When timelines slipped, the fault lines became clear. Business readiness was achieved, but systems were delayed. Systems were delivered, but the business was not ready to adopt them. The TMO carried delivery accountability, yet lacked the authority to resolve conflicts between the two. End-to-end ownership existed in principle, but not in practice.

This fragmentation became most visible in executive forums. The same initiative could be described as progressing well from a business perspective, delayed from a technology perspective, and misaligned from a strategic perspective — all at the same time. Each office reported accurately within its own lens, yet leadership was left reconciling multiple versions of reality instead of making decisive, forward-looking choices.

Importantly, this was not a capability issue. The teams involved were competent, committed, and often frustrated themselves. The issue was structural. These offices had been created incrementally, in response to emerging challenges, without an overarching enterprise design. Roles existed, but decision rights were unclear. Accountability was assigned, but interfaces between offices were never designed.

There was no shared interaction model explaining how strategy should cascade into delivery, how delivery should be coordinated across business and technology, or how progress should be measured consistently. Each office optimized within its own mandate, unintentionally reinforcing the very silos the organization was trying to break down.

Our attempt to address this did not start with new tools or dashboards. It started with clarifying roles, redefining boundaries, and explicitly designing how these offices were meant to work together. Governance was reframed from being office-centric to enterprise-centric. Particular attention was given to the handoffs — where accountability should intentionally shift from strategy to delivery, and from coordination to execution.

The experience reinforced a lesson I’ve seen repeatedly across large transformations: creating more offices does not automatically create clarity. Good intentions, when paired with incremental design, often lead to overlap, friction, and diluted accountability.

True maturity shows up when strategy, transformation, and delivery operate as one coherent system — with clear ownership, intentional interfaces, and a shared understanding of what success actually looks like. Without that, even well-meaning governance structures risk becoming busy, fragmented, and ineffective.

Closing Thoughts

Business PMOs, IT PMOs, TMOs, and SMOs are not the problem. The problem arises when they are established without a clear enterprise design, decision rights, and an interaction model that connects them into a single system.

If your organization is adding new governance layers to address delivery challenges, it may be worth pausing to ask whether you are solving the root cause — or simply redistributing complexity across new structures. Clarity of ownership, end-to-end accountability, and well-designed interfaces matter far more than the number of offices in place.

If you’re navigating similar challenges or reassessing how strategy and delivery are governed in your organization, I’d be happy to connect. Sometimes the biggest shift in delivery performance doesn’t come from adding another office — but from redesigning how the existing ones work together.